In 2008, ArcelorMittal found itself stuck between a rock and a financial hard place.

The mining and metals conglomerate launched an ambitious plan to upgrade a 1940s era iron ore complex in Nova Scotia by increasing annual production from 16 million tons to 26-30 million tons. Soon after, iron prices swooned, placing a massive pressure on budgets. To top it off, the company realised that the port couldn’t be easily retrofitted to fit newer, larger ships: it had been dug directly out of bedrock, says Michael Kanellos, IoT analyst, OSIsoft.

Undaunted, ArcelorMittal moved forward with what you could call the “Extreme Makeover: The Industrial Edition.” Instead of concentrating on new capital investments or construction projects, they chose to increase production by synchronising mining, grinding and logistics activities to see if it could squeeze more efficient production out of existing operations.

By 2015, the Mines Canada facility was producing 10 million more tons a year, the equivalent of $120 million (€110 million) in annual revenue. In one year alone, production increased from 23 million to 26 million tons by fine-tuning process steps – accomplishing that same 13% increase through capital could have cost up to $75 million (€68.8 million), according to Michel Plorde, director of systems.

ArcelorMittal’s story is one we’re seeing across the industrial world. Paper manufacturers like Verso and Fortress are modifying paper mills from the 1960s and turning them into facilities for specialised packaging and materials. Pasta makers, chemical reactors and other pieces of equipment (that are likely older than the median age of people reading this article) are getting solid state drives and Wi-Fi nodules grafted onto their side.

“We need to get user or existing grid more efficiently to expand capacity,” said Richard Glick, a commissioner for the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission at ACORE Renewable Energy Grid Forum. “There’s a lot of interest in Congress to include grid modernisation in an infrastructure bill.”

The trend to retrofit is largely driven by four factors:

Number one: Moore’s Law and the economic impact is still alive and well. Processors, sensors and other hardware continue to dramatically, steadily decline in price while increasing in performance. This has paved the way for better uptime and predictive maintenance. The pitch bearing— a set of bearing that angle wind turbine blades to maximise output — is often the cause of failures shut downs.

Waiting until it fails can lead to repair costs of $150,000 (€137,593) or more, but there are few visible cues to indicate a problem. Monitoring ongoing performance and predicating failures, Sempra Energy estimates costs associated with downtime and repairs by 90%. Orsted uses similar techniques to halve the number of boat trips necessary to service its offshore wind turbines, saving 20 million Euros a year.

Number two, and perhaps most importantly: retrofitting equipment can save customers money while serving as a revenue driver for manufacturers, to use new technologies to attach aftermarket value-added services to new or previously-existing equipment.

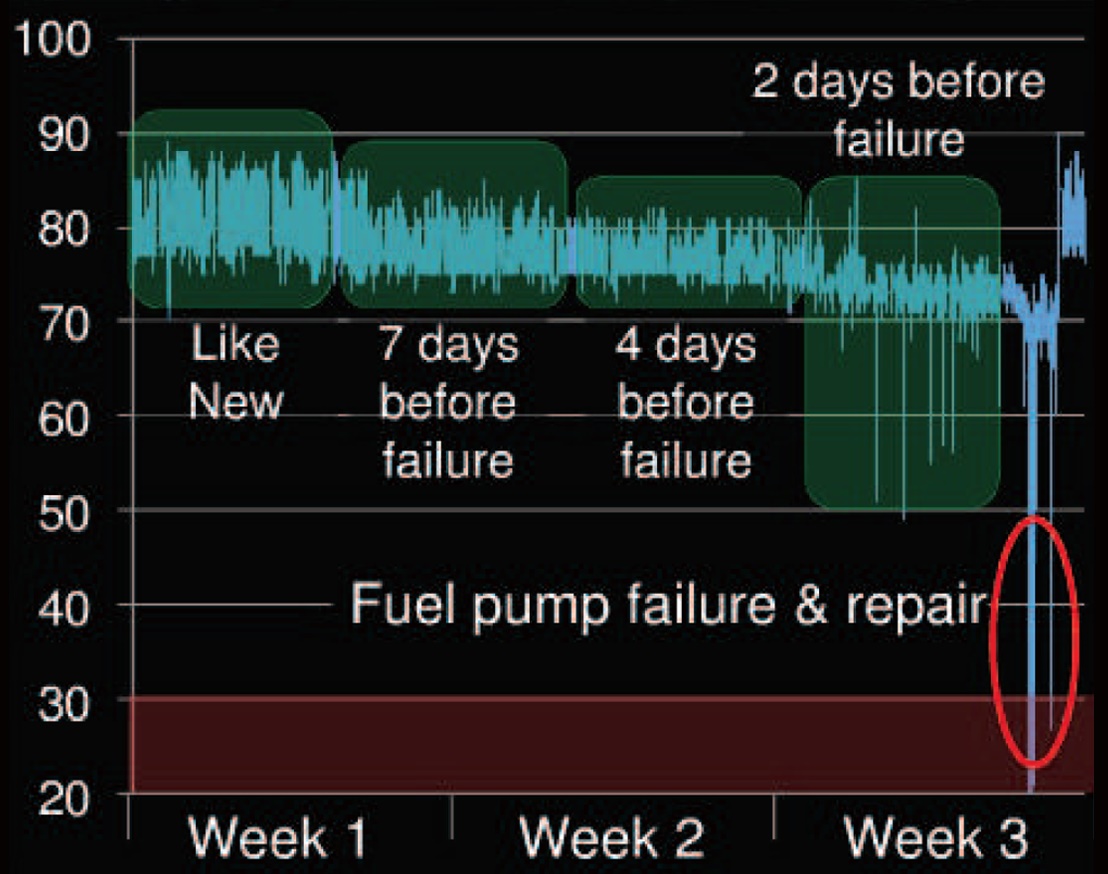

For example, Caterpillar’s CAT Connect services saves one shipping company $1.5 million (€1.3 million) per ship per year by sending data on fuel consumption and recommendations on operations improvements. Customers save money while Caterpillar and its dealers increase their revenue.

Number three, the financial sector has more power than it had years ago. Nobody wants to invest money in new capital unless they have to. Retrofitting old equipment with software delivers more rapid ROI than new equipment does.

And finally, number four: old equipment still simply works well! The average age of a transformer on the U.S. electrical grid is now 40+ years old. Tens of thousands of transformers are scattered across the U.S., ranging from $2 million (€1.8 million) to $7 million (€6.4 million). You’d be hard pressed to find any piece of equipment inside a data centre that is 40 years old, let alone a full data centre that old.

Michael Kanellos

Itaipu operates the world’s largest renewable power facility in the world, with a hydroelectric dam that produced 103 terawatts in 2016 – and is several decades old. To prolong its life, Itaipu invested in sensor systems that detect potential mechanical and structural issues early in their lifecycle, as well as systems for improving output.

We’re seeing interesting results on smaller scales too. J.D. Irving didn’t want to replace a saw that cut 60 foot long spools of paper into six-inch rolls of toilet paper, but it also wanted to begin collecting data from the 1970’s era system. With a wireless gateway and other technology, it developed a relatively quick, and inexpensive, bypass.

Turning old into new doesn’t solve every problem. A solid percentage of the gains in energy efficiency in homes and buildings over the past decade have come because new equipment is substantially better. Still, it’s often the best place to start.

I choose to live by this motto: when it doubt, don’t throw it out.

The author is Michael Kanellos, IoT analyst, OSIsoft

Comment on this article below or via Twitter: @IoTNow_OR @jcIoTnow

Leave a Reply